Fifth Avenue in 1907 was changing. Grand limestone, marble or brownstone mansions still lined the broad avenue; however the northward march of retail establishments was causing millionaires to flee further uptown, erecting chateaux and palaces along Central Park. Mansions were being demolished to be replaced by commercial buildings or transformed upper-class stores.

At 59th Street the Plaza Hotel was being completed, across from the imposing residence of Cornelius Vanderbilt II. This was the year that real estate investor Charles A. Gould commissioned Woodruff Leeming to convert his home at No. 714 5th Avenue to a six story commercial building that purposely blended with the homes of the wealthy who had not yet surrendered the battle.

Retaining its original 1871 proportions, height and style, the converted limestone facade mimicked its neighbors. The mansard roof continued the line of the former parsonage of the 5th Avenue Presbyterian Church to the south and the Zabriskie residence to the north; and the overall French style melded into the environment.

|

| photo NYPL Collection |

The design of Gould’s renovation was unique – the first two floors being a single retail unit and the third through fifth floors being treated as a whole -- essentially a wall of glass structurally and architecturally far ahead of its time.

As the building was being completed in 1908, Francois Coty was becoming rich in France with his perfume, La Rose Jacqueminot, introduced in 1904. By 1910 he was expanding and searching for an appropriate New York headquarters. He found it at No. 714 Fifth Avenue.

On August 31 of that year, in what it called “A further addition to the business interests on Fifth Avenue in the vicinity of the Vanderbilt houses,” The New York Times reported on “the leasing of the Charles A. Gould residence, 714 Fifth Avenue, through the Cross & Brown Company to a French perfumery firm. Alterations will be made at once preparatory to opening the house as a retail store.”

The newspaper somewhat nostalgically added, “This entire block, therefore, on the west side of Fifth Avenue, between Fifty-fifth and Fifty-sixth Streets, except the church property on the Fifty-fifth Street corner is now devoted to business.”

Coty signed a 21-year lease for the building paying between $20,000 and $25,000 per year.

Immediately after acquiring the property, Francois Coty commissioned the famous French glassmaker, Rene Lalique, to replace the wall of windows on the central floors. The extraordinary three-story work of art, reminiscent of the Art Nouveau designs that made the artist world-renowned, consists of intertwining vines and flowers climbing up the side windows while leaving the central-most panes clear. The overall effect of the composition could be appreciated only from the street. The windows, while not original to the design of the building, instantly became its most striking feature.

Coty occupied the three floor with the Lalique windows and subleased the first two floors to the Stage Society of New York and the top floor to various tenants.

As American doughboys returned from World War I they brought with them Coty perfumes and powders, creating new demand across the country. Coty’s American business skyrocketed. A factory and laboratory were built on Manhattan’s west side to avoid the importation tariffs. The factory was manufacturing, by 1929, 23 different perfumes and a seemingly unending list of other cosmetics and toiletries.

Coty renewed its lease in 1931; however a year after Francois Coty’s retirement in 1940, the firm moved to 423 West 55th Street. The building, however, would continue to be referred to as The Coty Building.

A heated battle broke out between preservationists and developers when in 1985 a plan was unveiled to erect an L-shaped, 44-story office tower with entrances on West 56th Street and on Fifth Avenue. The plan would necessarily involve the demolition of Nos. 712 and 714 Fifth Avenue.

The Municipal Art Society took up arms and petitioned the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission to landmark the building. When the Lalique windows were brought to the attention of the Commission, it agreed to schedule a hearing.

The Commission designated the Coty Building a landmark; but on May 28, 1985 it also approved a Certificate of Appropriateness for the tower to be built behind them, incorporating the facades of the two former houses.

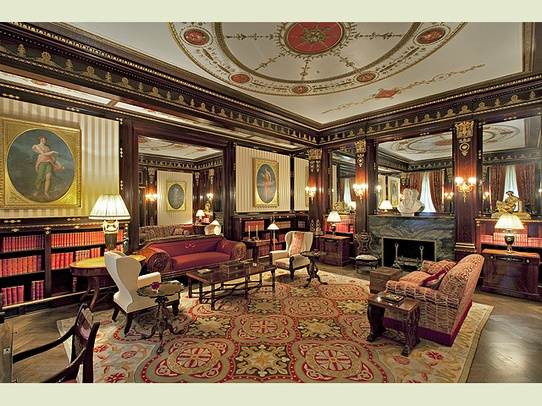

Between 1989 and 1990, architects Beyer Blinder Belle restored the façade and renovated the interior as the flagship store of Henri Bendel. A four-story atrium replaced the former Coty offices and, for the first time, Rene Lalique’s exquisite windows could be viewed as a whole from an inside perspective.

Jerold S. Kayden, in his “Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience,” wrote, “Although such hybrid preservation efforts disturb some advocates of historic preservation, they enjoy the support of others who believe that a balance between development and preservation is politically and economically essential in modern cities.”

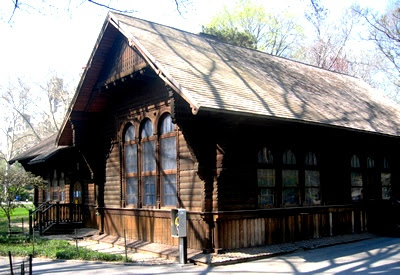

Image Emilio Guerra

The passerby may not notice that nothing is left of the Coty Building other than its façade. The copper-clad roof and dormers, the soaring two-story retail entrance and Rene Lalique’s unique and priceless windows appear much as they did in 1910. Only by entering the threshold does one enter the 21st Century.